The Fingerprint Part 2: The REAL Comeback

In the first post in this series, The Fingerprint, I ended by asking the question: How can the language of the fingerprint return to architecture? The fingerprint is a metaphor for hand craft.

In the New Amsterdam Theater, nearly every part of the interior was hand-crafted. Today nearly every part of a building is factory manufactured. I liken hand-crafting in architecture to a language that we have lost the ability to speak or write. Hand-crafting is indeed a language, a rare one for sure, but it is not lost.

We know the beautiful sound of it whenever we hear it.

As I was growing up, I was always making things with my dad (a floating dock, a picnic table, a work bench, etc.). He taught me the love of making things with my hands, but it wasn’t until I met a fellow architecture student named Ken Manaugh that I really began to understand what it means and what it takes to be a craftsman.

Ken and I were classmates and friends attending Kansas University’s School of Architecture together. In our final year, Ken’s thesis was a design/build project. He designed and constructed a small cabin behind Marvin Hall. It was an incredible building with elegant proportions and an amazing array of sophisticated details. I remember watching the building go up as the semester progressed and being mesmerized by the slow, deliberate act of making. Ken would draw several design options of the many parts and pieces of the cabin and then decide which one was best. He would then go down to the school’s wood and steel shop and begin making. He made everything in the cabin by hand, even the door hinges, lever, and locking mechanism. The smallest detail was meticulously thought through, attended to, and handmade.

I was inspired and became more determined to learn the craft of making.

It would be years later that Ken and I would reunite on what would become a special journey into the world of hand-crafting. I was working in New York City for an architectural practice when Ken called me and said that he had a dream client. He explained that a client wanted him to design and build several new structures on their century-old lakeside property in northern Wisconsin. The structures were to be a sauna house, boat house, and outhouse (yes, an outhouse: the property did not have running water).

I couldn’t resist. I gave my two weeks’ notice the next day, and much to the dismay of my boss, colleagues, parents, and friends in NYC, I left to begin the dream project.

Ken lived in a small apartment in Chicago that had one unique feature: a fully equipped basement wood and steel shop. We accessed it through a trap door in the floor of one of the bedrooms. It was tiny, but effective.

After a day spent looking at the maps of the property and seeing photographs of the existing 1901 original log cabins and the surrounding old growth Hemlock forest, I was hooked.

As young architects and aspiring craftsmen, we were reacting to the “fast food” world of speculative development. With few exceptions everywhere we looked, we saw cheap, poorly constructed buildings. We sought after and researched buildings that had been made by local craftsmen and had stood for a long, long time.

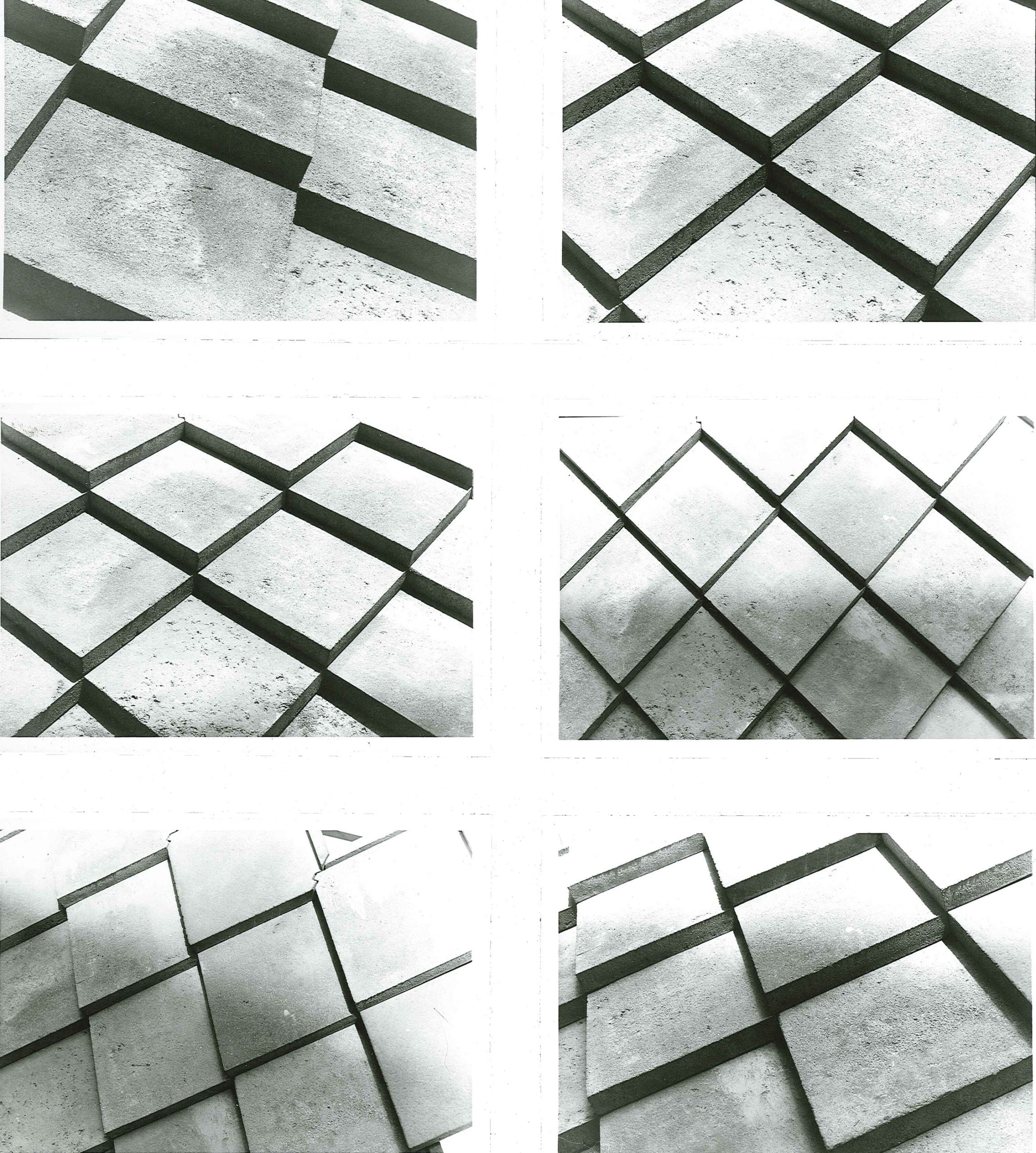

The research led us to some of the small towns and villages of Bavaria, Germany in the Staudach district. What were of keen interest were the roofs. Many of the original roofs in this district were perfectly intact and over 175 years old! (that’s not a typo: the roofs are 175 years old).

The interesting thing is that these roofs were made of concrete. Concrete tiles, to be specific. We learned as much as we could about how these original tiles were made and what their secret was. We found the fingerprint here, in the roofs of Staudach.

We decided that the roofs of our buildings were going to have concrete roofing tiles. After all, who wouldn’t want a roof that lasts 175 years!

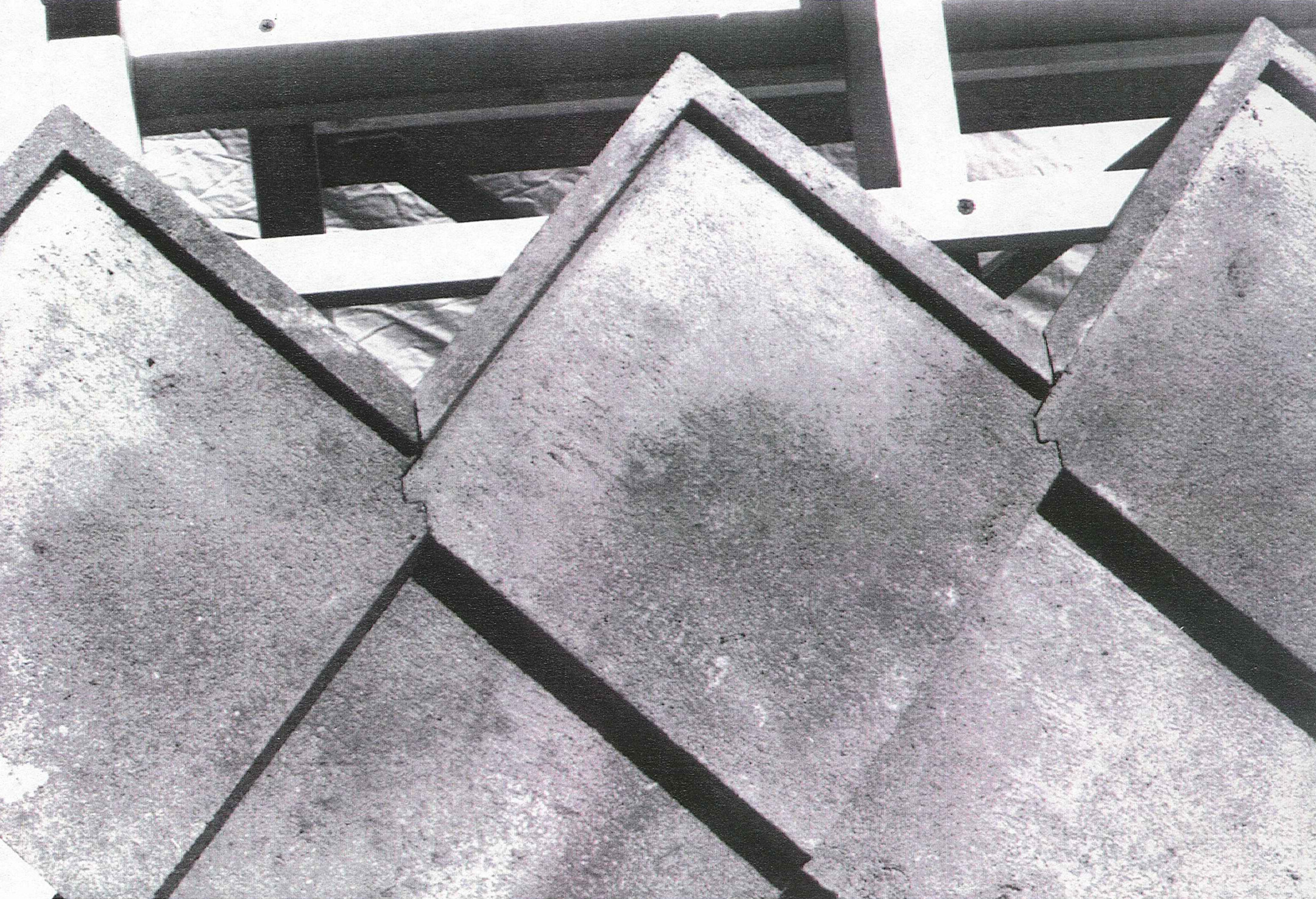

We spent months experimenting with the concrete mix. Water, cement, type and size of aggregate as well as various admixtures became the ingredients of our recipe for longevity. Dozens of concrete tile test samples sat around the house, oven, refrigerator, and freezer as we tested their strength, durability and porosity. After many months and recipes, we finally found the right one. With the help of micro-silica and a super-plasticizer, our concrete had an almost granite quality: incredibly dense, water-proof and durable.

After getting the concrete mix right, we began to design the tile. We settled on a diamond-shaped style that had interlocking sides, tops, and bottoms.

Maybe we did it all backwards, but after the concrete mix and tile type design, we figured out how to “mass produce” the tiles.

We needed to design a press to fabricate the tiles. After many mock-ups and failures, we finally arrived at the right design, and we handcrafted it. It is a press with various tile forms that allows us make 30 tiles at a time. It is crafted entirely from steel with hard wood inlays in the legs and handles.

The concrete is poured into the form, screeded, and then lifted out for curing. It is a laborious, time-consuming process that requires one special ingredient: a commitment, a love for hand-crafting.

Today, JEMA has made several modifications to the design of the tiles and the press. We will be using the concrete tiles for a client’s house in rural Missouri. I look forward to seeing the moss grow on the concrete tiles until they are covered in a lush green. And perhaps, in 175 years, someone will discover the fingerprint once again.

A special note: the fingerprints on this press and on these tiles are those of my friend Ken Manaugh. He is a true craftsman and I am grateful to this day that I learned from him how fundamental the “fingerprint” is to the practice of architecture.