Winston Churchill the Architect?

In the first post of this series, we looked at culture and its relationship with architecture. In this post, we will touch on another fundamental relationship: being and architecture.

So to be clear, Winston Churchill was not an architect, but he had a profound understanding of architecture. Much has been written about Churchill and his legacy as a statesman, leader, writer, historian, and even painter, but in all of this literature and analysis, you will not find any serious discourse on his relationship with architecture.

Churchill did not write or speak much about architecture, but like some of the great philosophers of the world, the little he did say exhibits the depth of his understanding of the potency of the built world. His one statement hardly seems radical at first glance, but the fact that he was able to distill the essence of architecture into three sentences is remarkable. Perhaps the depth of his understanding was created by the great expanse of his experiences. We will never know why he uttered these famous words, but we do know that he spells out very clearly the impact architecture has on humanity – on us. Churchill said:

“There is no doubt whatever about the influence of architecture and structure upon human character and action. We make our buildings and afterwards they make us. They regulate the course of our lives.”

Winston Churchill, addressing the English Architectural Association, 1924

Dwelling within this quote resides a singular subject that has long since been overlooked and perhaps even forgotten within the field of architecture. It is a subject of importance in the sense that its very nature determines our nature. Its characteristics echo who we are and in turn, we continually evolve within it. The subject I am referring to is being.

Churchill was tackling what Plato, Aristotle and (skip 1000 years) Heidegger were all trying to explicate: the mysterious phenomenon of being. Asking what the nature of “is” is sounds strange and that’s because it is strange. We use the word “is” all day every day without stopping to think about its true nature. Why is there something, rather than nothing and how, as Churchill says, does our “is”, our being, relate to architecture?

Perhaps “is” is our greatest mystery, a mystery right under our noses. The Chinese proverb “the darkest place is under the lamp” is apt here.

We know that the environment (color, proportion, texture, light, etc.) has a proven impact on our behavior. But this discussion has taken on new life since the transformation of our environment from human-centric to auto-centric in the last 60 years. Our world has changed insidiously and dramatically in the 20th and 21st Century. Along with these environmental changes, we ourselves have transformed. What our being is has changed rather profoundly. How so?

Our being is determined by relationships. We are always already born into relationships. We relate to our surroundings even before we are born: sounds, movements, and emotions are all felt by us in the womb. From there, relationships drive our being. Relationships with the “other” (our parents, siblings, friends and others) start the process of our own unique and collective nature of being.

Our relationship with the natural world is another essential developer of our being. The sun, sky, rivers, trees, meadows, and our interaction with them determine our nature.

What else drives the nature of our being?

There are two other relationships that determine our individual and collective being: technology and buildings. Technology and being will be covered in a future blogpost, but by buildings, I mean our constructed world: the roads, bridges, homes, buildings and communities that constitute what we see, smell, hear and touch everyday all day.

Yes, the nature of our being is determined to a large extent by our constructed world. From his three sentences on architecture, Churchill knew it.

How we have evolved as a community of beings is directly related to what we have built up around us. Architecture is the constructed reflection of our values. As a physically manifested snapshot of our culture, architecture “returns” as one of the great regulators of our being. We have a deeply causal relationship with our constructed universe and nothing we build is neutral; every single construction has an impact on our nature. As buildings are, so goes our “is”.

Architecture is a unique “regulator”. Residing within our constructed world lies the always shifting, always evolving nature of our being. Unlike the Other and Nature, architecture forms a kind of dance with being where cause and effect slip back and forth, in and out…one is leading the dance, and at the same time, one is following.

We must ask ourselves these “Churchillian” questions:

-

Have we underestimated the potency of our constructed world’s reciprocal force?

-

Do we fully understand architecture’s influence on our being?

-

How has our architecture shaped the character of our being?

We must do some unearthing to see how architecture has “made” us. Here are two potential insights into our architectural “shaping”:

-

According to a recent study by Charles Courtemanche, a health economist at Georgia State University, there is growing evidence that obesity is linked to what we live by, specifically, “big box” retailers.” What they found was that the density of restaurants and large-scale food retailers in particular areas was a major factor between 1990 and 2010 in the nationwide rise of obesity and BMI, or body mass index, which measures weight against an individual’s height. They attribute nearly half the rise in severe obesity — referring to people who are more than 50 percent above their ideal weight — to such businesses.” What is compelling about this research is the insidious quality of our built environment’s influence on our body. We build the restaurants and big box retailers and then begin to be shaped by their very presence. And despite all of our knowledge about nutrition and exercise, we are rendered nearly powerless by the presence of their “is”. In 20 years, the density of big box retailers has ballooned. So has our waist line.

-

In their paper: “Social Life Under Cover: Tree Canopy and Social Capital in Baltimore, Maryland”, Meghan T. Holtan, Susan L. Dieterlen, and William C. Sullivan shed light upon the impact that connected tree canopies have on our social and communal lives. The findings are rich and striking. According to the article: “Tree canopy functions as a green web that has ecological, economic, and, we would suppose, social benefits. Tree canopy creates opportunities for interaction at the street level by increasing use of the streets as people are drawn outside their homes”. The research indicates a difference between “green space” and tree canopy, this is important since it appears that mature urban tree canopy (not “green space”) is the differentiating “shaper” of our communal life. The authors go on to say: “perhaps neighborhoods with greater tree canopy cover provide stress reduction. Neighborhoods with higher levels of tree canopy create a feeling of escape that is essential to mental restoration.” The research suggests that a mature, connected tree canopy has a significant effect on shaping and regulating our own feelings of civility.

Later in his life Churchill returned to architecture one final time. After Hitler’s bombs destroyed England’s House of Commons, there was vigorous debate on how to rebuild the structure. Churchill wanted to rebuild the historic structure exactly the same as it was. He believed that the building’s shape played a significant role in actually creating Britain’s form of government. He said, “we shape our buildings, and afterwards they shape us.”

Indeed, we are the “is” of our buildings.

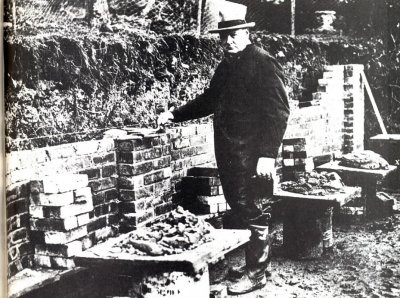

Like Churchill’s expansive resume–as a soldier, politician, writer, bricklayer, painter, to name only a few–we have to look at diverse and unexpected sources to begin to understand how what we build, our architecture, changes the very “is” in our being. Only when we see the shaper in the shape, will we begin to create environments that change our being for the better.