The Source of Sacrifice

In case you missed it, read Part 1 “Finding the Source” here

The next day at studio, we all discussed our day at the farm in Rosebud and what we learned. One student said that for the first time, he understood what it meant to take something for granted. I knew this student spoke from his heart and had experienced a transformation. I shared with the class one of my favorite quotes by Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature is a language and every new fact one learns is a new word; but it is not a language taken to pieces and dead in the dictionary, but the language put together into a most significant and universal sense. I wish to learn this language – not that I may know a new grammar, but that I may read the great book which is written in that tongue.” The students were indeed learning a new language. As the studio progressed, we pressed deeper and further into this new language.

The disruption, destruction, and degradation of the forest that was necessary to harvest enough stone, wood, and clay for sixty students had made a powerful and enduring impression. Each student regarded “their” pieces of stone, wood and bucket of clay in a different way. A respect, even a level of reverence, for the stone, wood, and clay was born that day down at the farm.

Satish Kumar, a Deep Ecology philosopher, says that “life is sacred precisely because it sacrifices itself in order to maintain and continue life.” He uses the example of the seed: it sacrifices its own body in order to transform into another life form. Bringing the students to the farm was essentially an effort to have them experience firsthand the sacrifice of the source. Seeing, feeling, touching and even smelling the “unearthing” was powerful and had set the tone for the whole studio. My personal goal was for this experience to set the foundation for these students’ careers.

Now that each student had the source materials, we began the design projects.

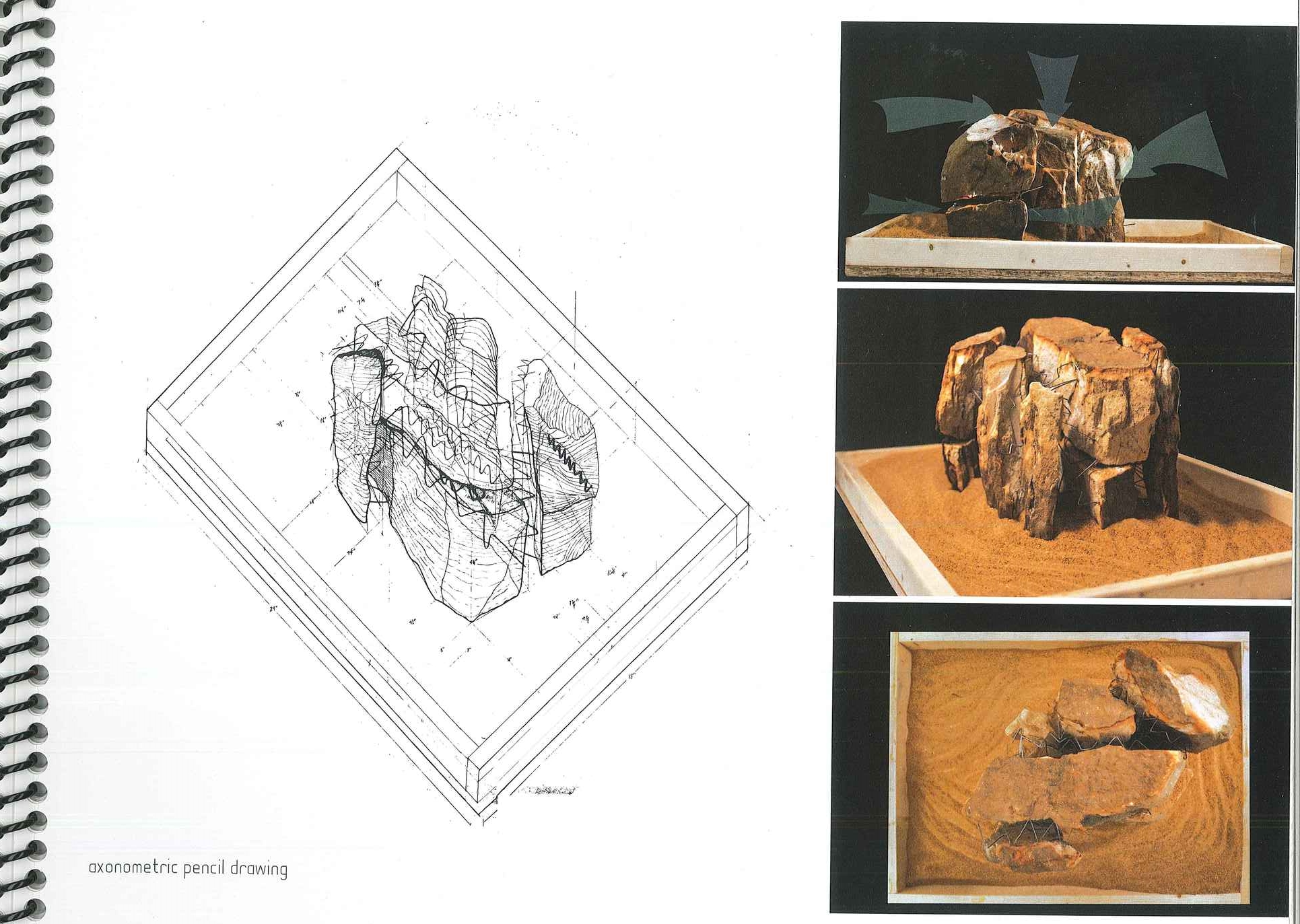

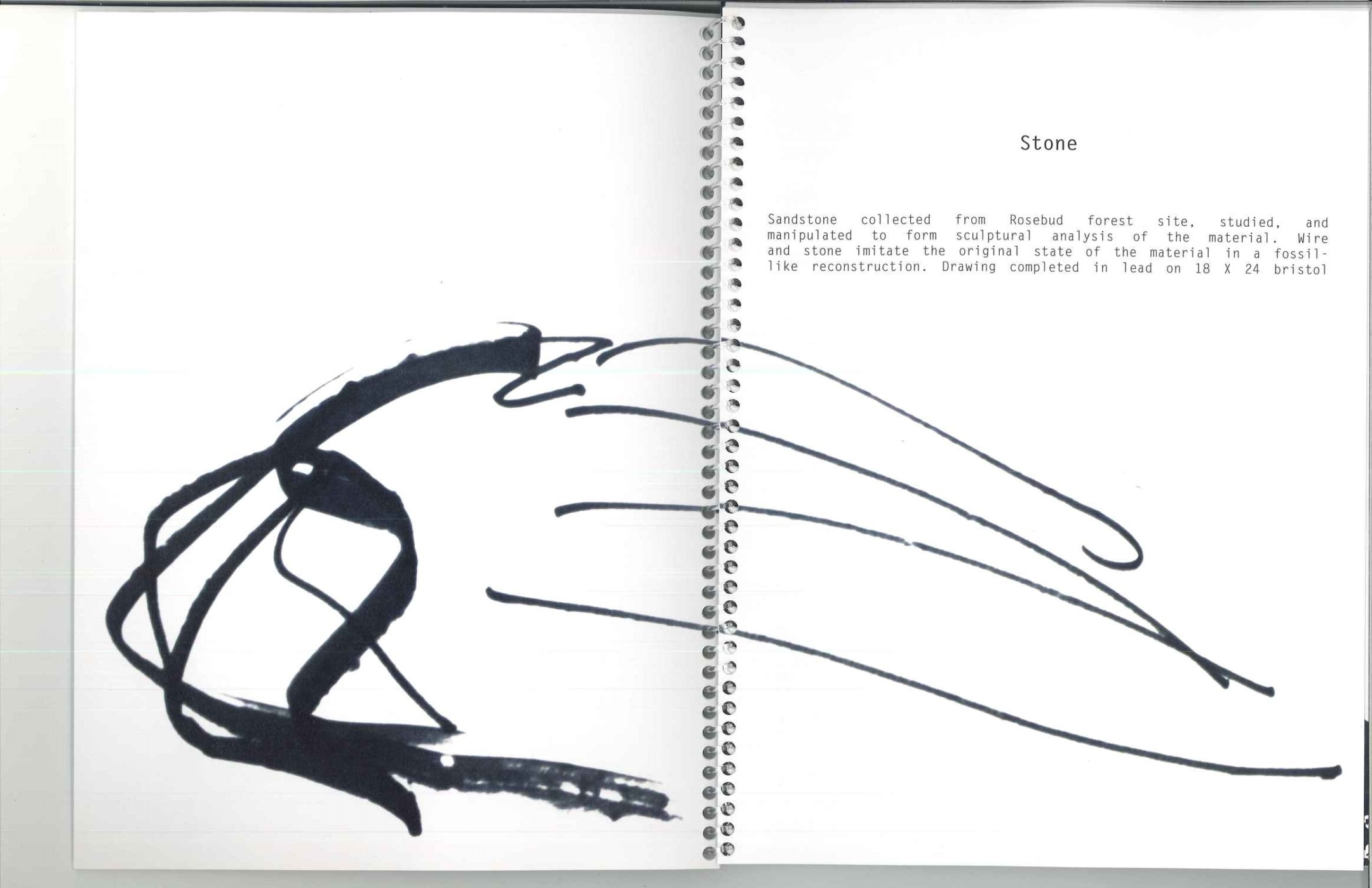

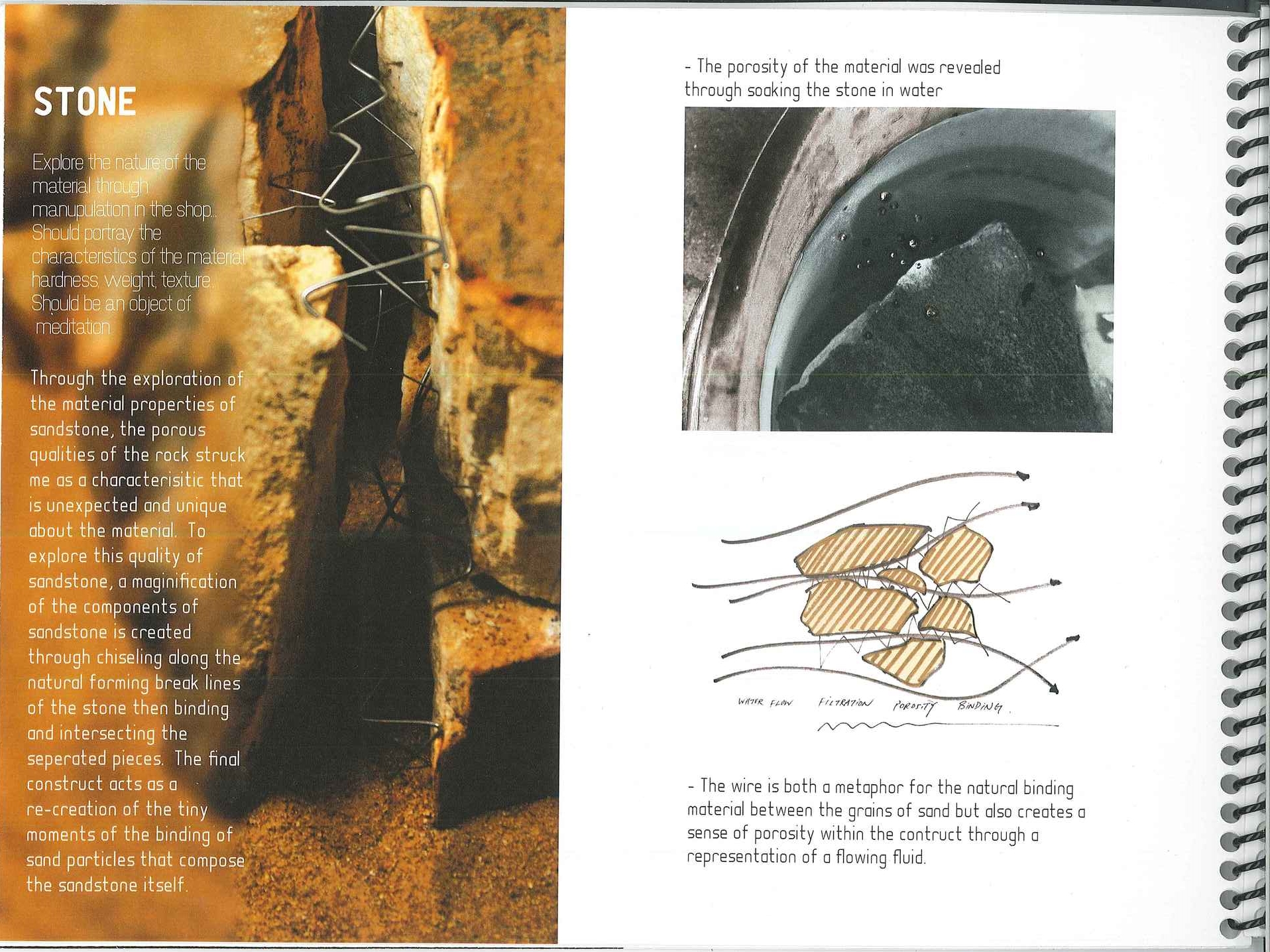

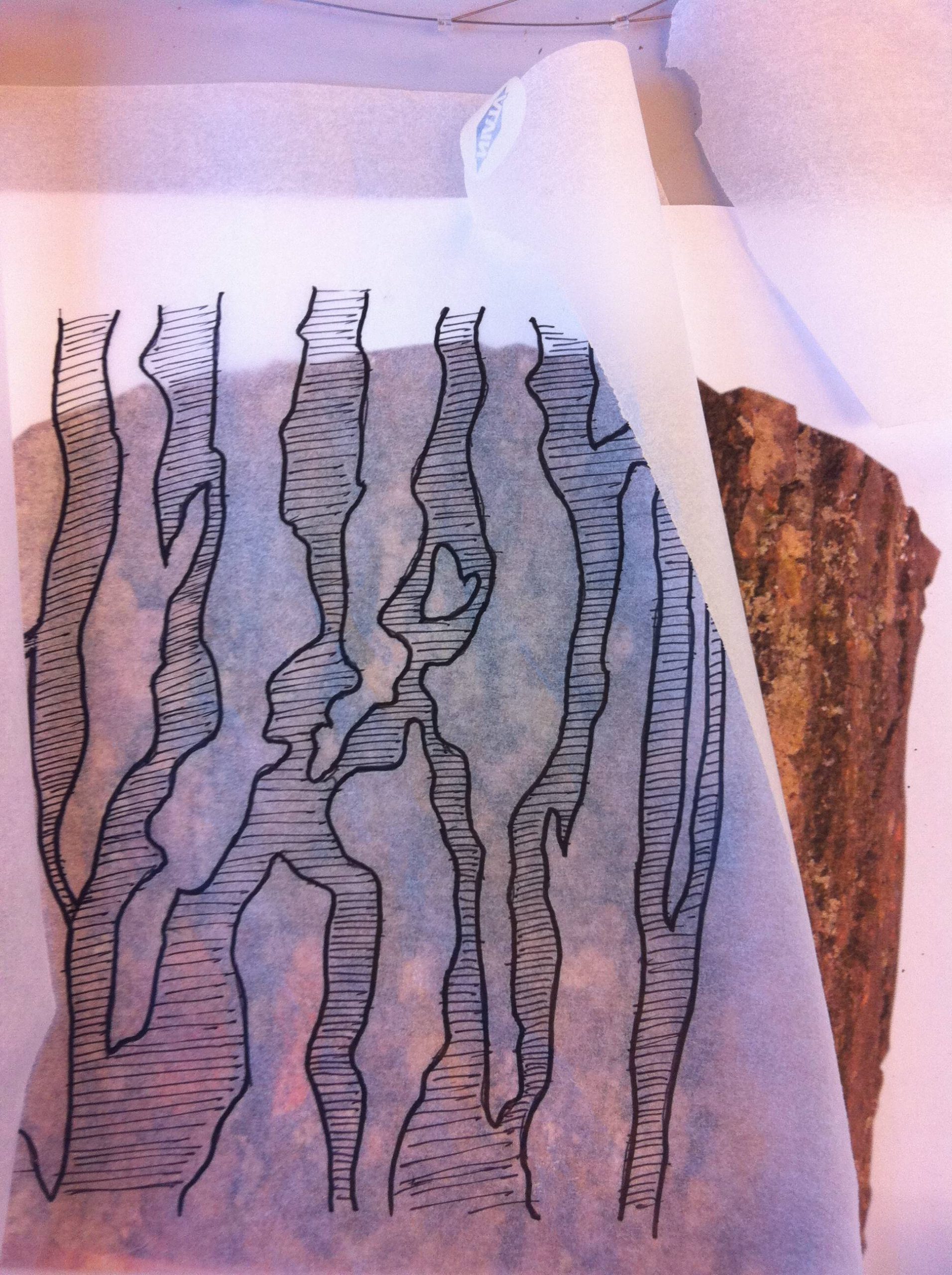

First up was Stone. Each student constructed a 24” x 36” x 2” wood box in which they had to create a stone “sculpture.” Along with their stone segment, they could use two other materials: sand and wire. The duration of the project was two weeks. Dean Bruce Lindsey and Leland Orvis were incredibly supportive and bought a masonry wet saw, dozens of stone chisels, hammers, and protective eye gear. The shop was buzzing day and night with the sound of the stone being cut, chipped, and chiseled. The resulting work was amazing. See below for some of the students’ projects in progress and final products.

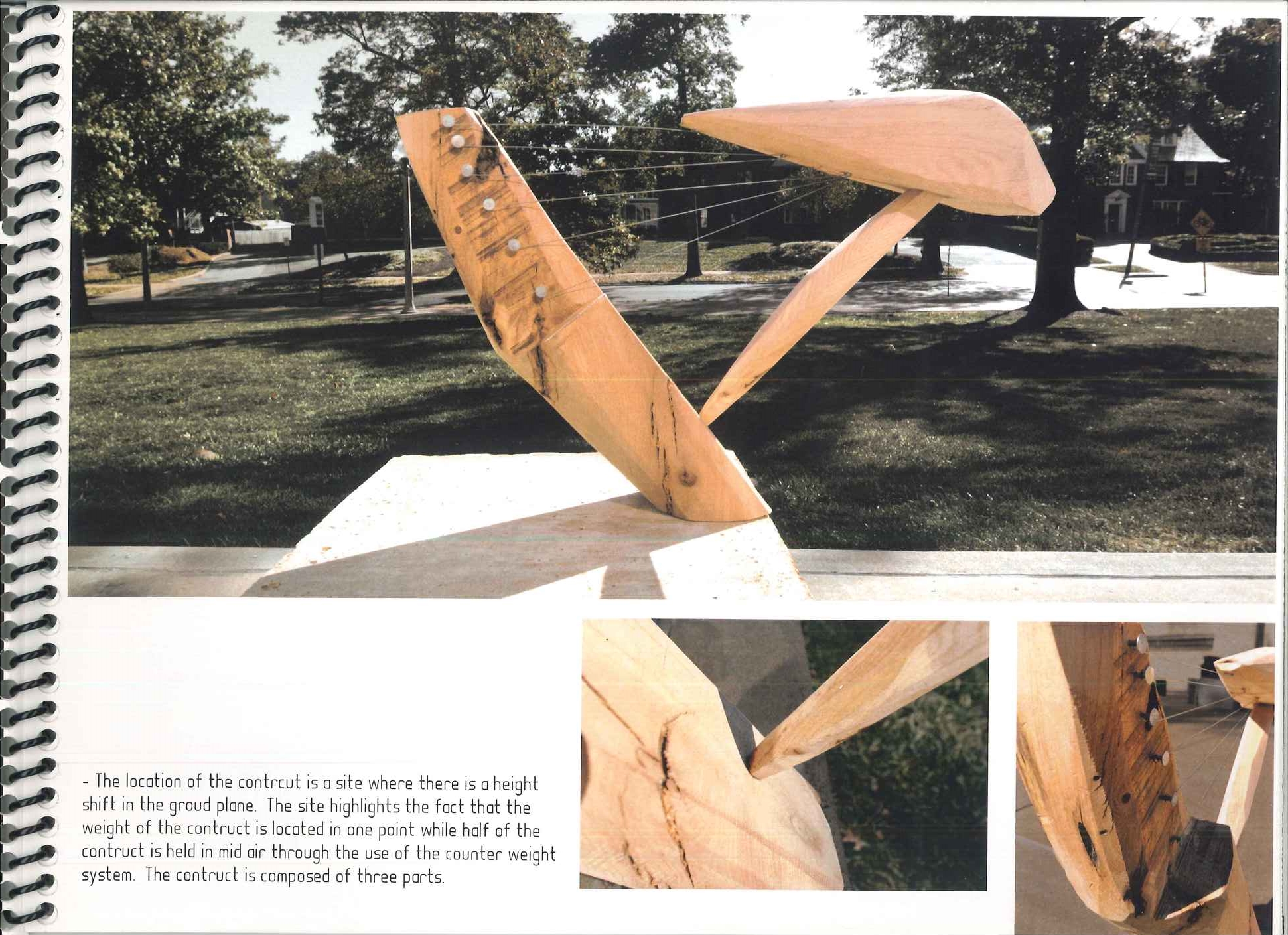

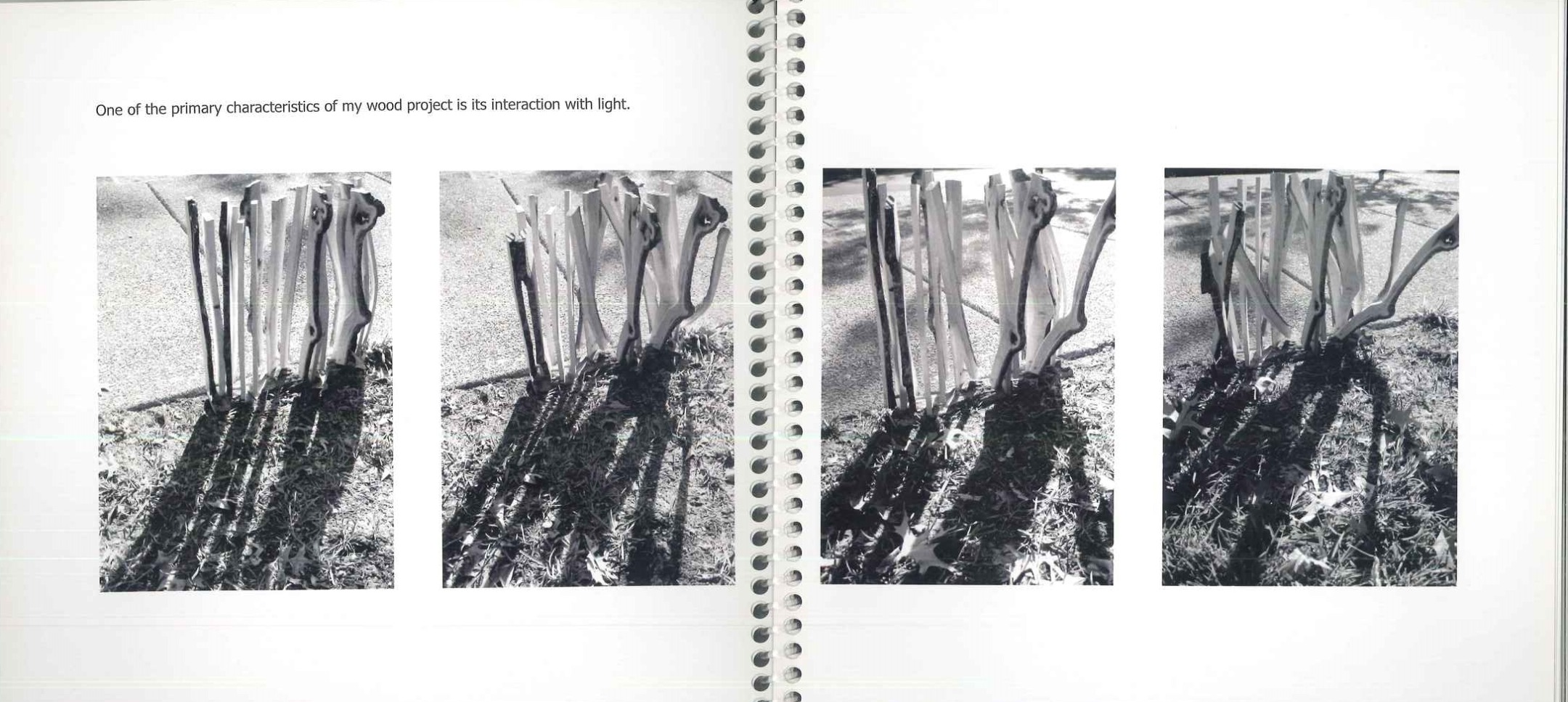

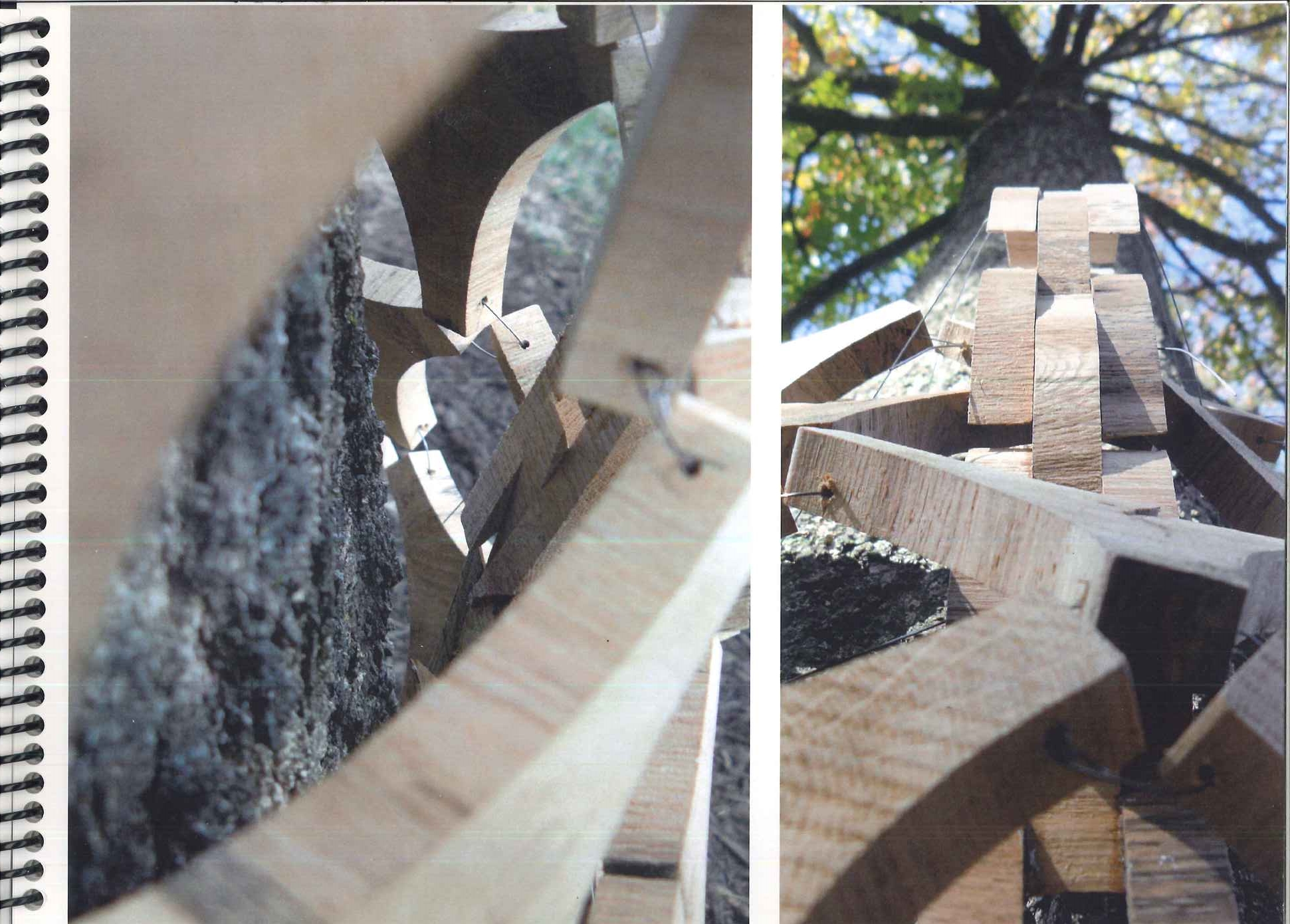

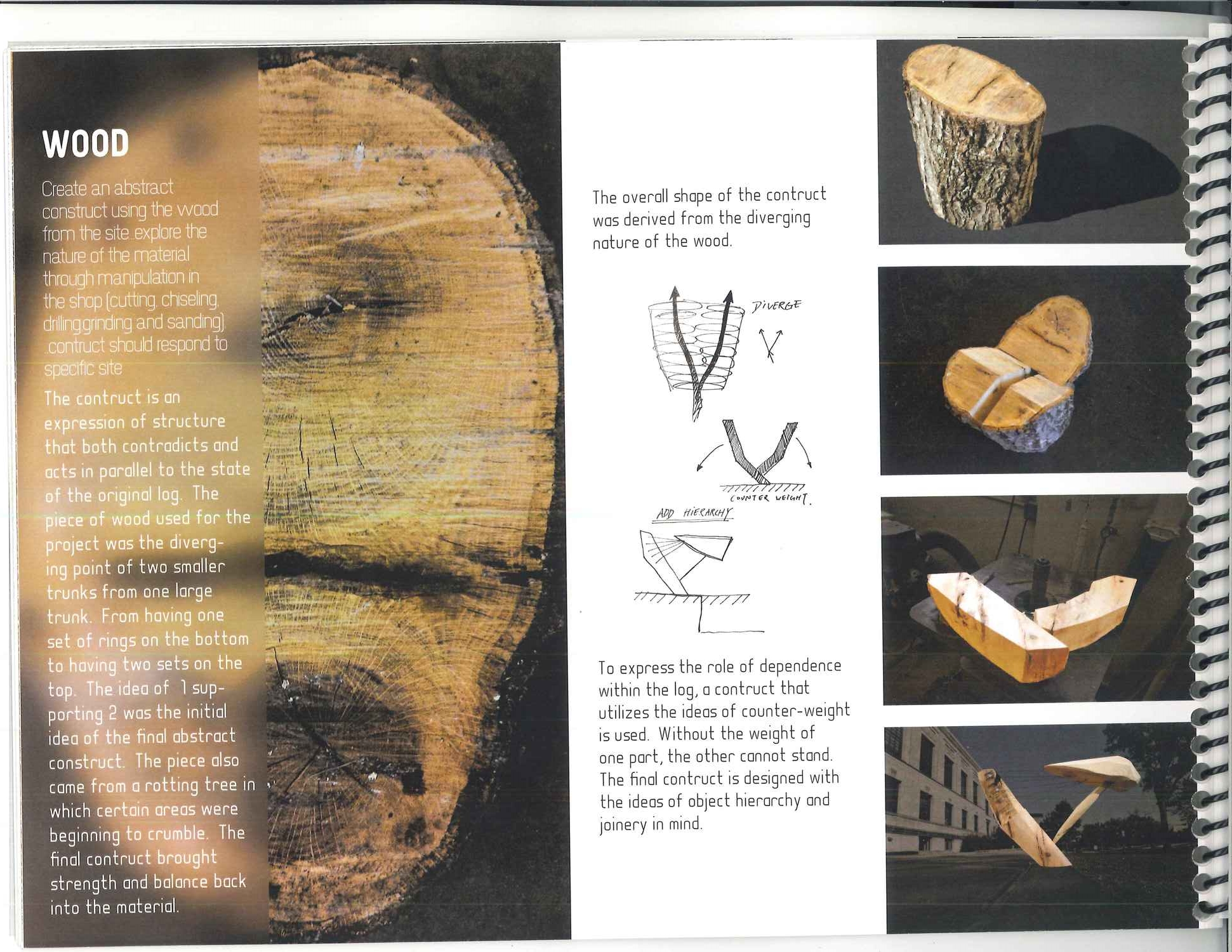

Second was Wood. Again the timeline was two weeks. Since the wood was “whole” (small to large segments of whole tree), Leland had to design and build a custom jig that stabilized the large logs while they were milled with the band saw by the students.

Because the wood was in its natural state (not a 2 x 4, etc.) the students’ imagination was freed of the constraints that come with using dimensional lumber. When we work with dimensional lumber, its size and linearity implicitly shapes our thinking. Many of the students approached their wood segments as a sculptor would approach a block of stone. Carving, chiseling and drilling, as well as sawing and milling, were all utilized. The wood’s grain, bark, color, porosity, shape, texture, and structural capacity were analyzed. Again, the results were inspiring.

Third was Clay. Same process and timeline. Same great results.

The intention for these three hands-on design projects was not only to engage the students’ design skills, but more importantly, to re-establish a relationship between each student and the source material and its sacrifice. The hands-on is what was important here. Sourcing, handling, cutting, chiseling, and shaping these materials with one’s hands is the first step in understanding their intrinsic value and essential qualities. The understanding and respect of these natural resources is the only way towards a new frontier of dwelling where we design and build with awareness, respect, and gratitude.